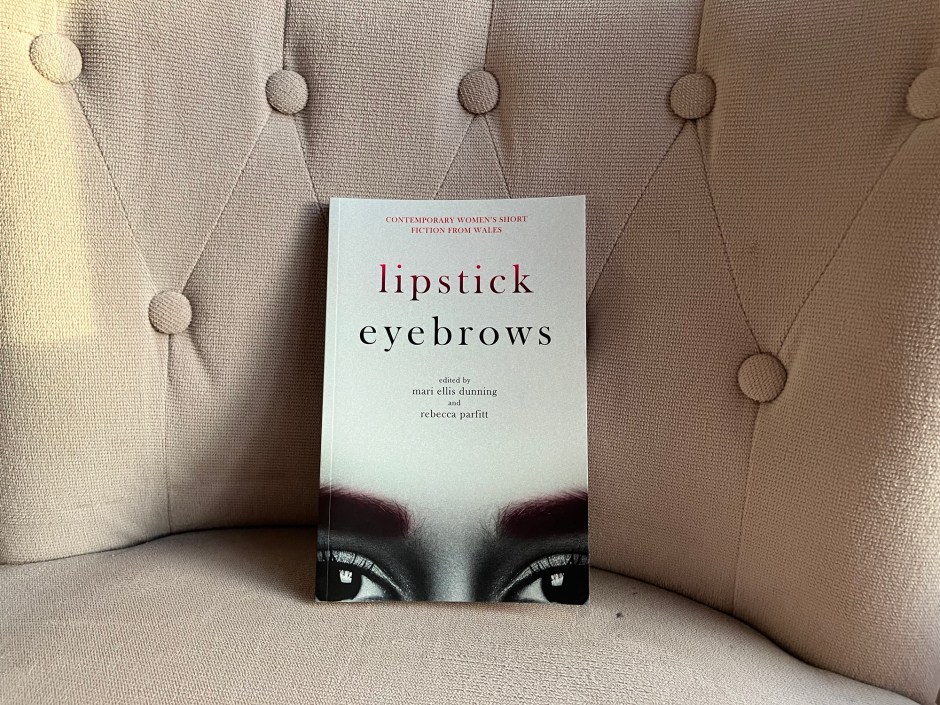

One of my short stories, ‘Something about Weddings’, came out last month in a collection called Lipstick Eyebrows, released by the Welsh publisher Honno. I won’t lie: it was very exciting receiving my complimentary author’s copies in the post, and flipping through to see my name printed on page 81.

This short story, which I sent in response to a call-out earlier this year, is one that I started writing in December 2016. I was a PhD student in Creative Writing at Cardiff University, still at the start of my journey, and I’d been invited, along with the rest of my cohort, to go to Gregynog Hall, in mid-Wales, for a writing retreat. Two and a half days of writing workshops, of lovely food, of exploring the grounds and taking advantage of our free time to write.

I had been to Gregynog once before, but it was different as a PhD student, less regimented. As an MA student, I sat in a classroom for long stretches of time, being taught various things and encouraged to write and experiment. As a PhD student, I took a walk with a friend and watched the horses in the nearby fields. I explored hidden nooks and corners of the old house, found tucked-in places to write.

I began the first version of this story sitting at an old wooden table, in a common room which smelled of pine. The flames in the fireplace cast dancing reflections across the polished floors. That night, at the open mic organised for staff, PhD and MA students, I read out the opening section. It was an unusual feeling, being pleased enough with a story to throw caution to the wind, and expose its raw, unformed shape.

There are still traces of what I read then lingering in the collection published by Honno, but the overall shape of the story is quite different. Over time, and with each rewrite, things emerged and others disappeared. In my initial draft, the protagonist, Claire, was more melancholy, and her relationship was entirely hopeless. The story was darker, more fatalistic. In a workshop, some years later, my friend – the brilliant US poet Christie Collins – suggested that Claire could have more agency. ‘I’d like her to take things in her own hands,’ she said in her gentle, tactful way.

That was a turning point for me. I went back to the story, thought and thought about it, and it transformed. Claire escaped. Instead of staying trapped inside, she went out. She made a friend. She came into her own. Other characters disappeared, family members who played minor parts, whose sole purpose had been to add a sense of realism.

Letting go of a story can be a bittersweet experience, but it wasn’t the case here. I feel truly happy that after all these years, this tale has finally spread out its wings and taken flight.